“There ought to be a law!”

Perhaps more than any other modern era, Americans today are obsessed with the proper role of law. Some citizens, old and young, lament the loss of a long ago time of some unified, less partisan, less divided polity. Whether that has ever been the case in our past (it hasn’t, by the way) the minds of people of all ages cannot help but occupy themselves with the question of the law and the proper role of government.

In modern news, the rise of figures like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez has once again thrust the concept of so-called “democratic socialism”, as though democracy or socialism on their own have been smashing successes. And San Francisco’s recent plastic straw ban has inspired countless conversations and humorous images to be created and shared ad nauseum.

But the fundamental divide throughout history in political discourse has ultimately boiled down to pretty simple questions: what is the nature of government, from where does it draw its authority, and what constitutes a just law. As it turns out, these questions have answers that, though hotly disputed, are rather simple and straightforward.

The Short Answer

Like all great questions and their associated answers, they have a relatively simple surface with a great depth of reasoning tucked underneath and this is no exception. But for those who may not have the time or inclination to start from the bottom up, I will save you the frustration and offer the aforementioned question at the outset.

The only relevant question to ask when considering any law is this:

“In imposing this law, would I be personally justified in enforcing it? And likewise, given any potential punishment for its violation, would I be personally justified in carrying that punishment out?”

Now this concept can be difficult to word concisely so let us bear out an example for illustration. Let us suppose that I proposed banning the possession or use of a substance like marijuana. In this instance, if I were to witness an individual possessing or using marijuana, would I be personally justified in confiscating that substance, removing that individual from their home and family, and placing them in a cage? Or, if in this instance a fine is imposed, would I be personally justified in taking that money or demanding it be paid under threat of force?

My suspicion is that response to this question is likely to be split. Many will immediately recognize its legitimacy and the underlying logic, most likely due to their being exposed to similar ways of thinking in the past, while others may be left a bit lost and confused. But the basis behind this question has a long history that should interest both groups and if that interest is piqued, please read on.

From Rights Onward

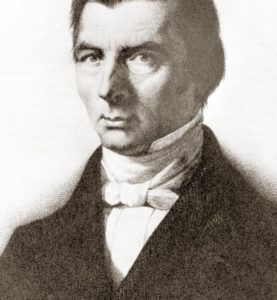

There have been many wise and influential authors who have blessed us with a thorough understanding of the nature of the law and government but my personal favorite is Frederic Bastiat. Born in 1801, his life was poised during such a time as to witness massive transformations in French culture, having been transformed from a monarchy to a unitary republic and empire under Napoleon. In his 30’s he became politically active and near the end of his life, his pamphlet “The Law” was published. “The Law”, perhaps more than any other work of political philosophy, contains the most succinct and logical explanation of how human rights proceed to form the basis of the human political life.

There have been many wise and influential authors who have blessed us with a thorough understanding of the nature of the law and government but my personal favorite is Frederic Bastiat. Born in 1801, his life was poised during such a time as to witness massive transformations in French culture, having been transformed from a monarchy to a unitary republic and empire under Napoleon. In his 30’s he became politically active and near the end of his life, his pamphlet “The Law” was published. “The Law”, perhaps more than any other work of political philosophy, contains the most succinct and logical explanation of how human rights proceed to form the basis of the human political life.

From a firmly Christian worldview, Bastiat begins his basis affirming that life itself is a gift from God Himself, with all its related aspects. And the inherent rights of humanity that proceed from life, that of “life, faculties, [and] production” undergird the basis of human political reality. Indeed, Bastiat states that:

“individuality, liberty, property — this is man. And in spite of the cunning of artful political leaders, these three gifts from God precede all human legislation, and are superior to it.”

It is from this pretext that Bastiat begins to lay the groundwork for the authority and legitimacy of political organization and the law itself.

Law Rooted in Defense

It has been stated here before that our human rights extend from our intrinsic human nature and that all rights are an extension of our core right of self-ownership, or as Bastiat puts it, “individuality, liberty, and property.” So if we are entitled to our rights and the extensions thereof, it naturally follows that we may defend those rights and this is Bastiat’s conclusion as well, as “each of us has a natural right—from God—to defend his person, his liberty, and his property.” In powerful succinctness, Bastiat declares,

“What, then, is law? It is the collective organization of the individual right to lawful defense.”

Wherefore, Then, Government?

So, with the former in mind, we ask ourselves: what grounds the basis of government given the nature of law?

We will often hear it quoted that the ultimate function of government is to protect the rights of its citizens. This is certainly an American understanding and it was held by many of its founders. James Madison is quoted as recognizing that,

“Government is instituted to protect property of every sort; as well that which lies in the various rights of individuals, as that which the term particularly expresses. This being the end of government, that alone is a just government which impartially secures to every man whatever is his own.”

Many so-called “Constitutional Conservatives” often look to a vague notion of “limited government” on the basis of a system laid out by the US Constitution. Many libertarians may extend that notion to one of an even more limited government, depending on their preferences. And most “extreme” anarchist libertarians or voluntarists will advocate for no organized government at all.

We should also make the distinction between “government” and “laws” as many will see the two as almost synonymous. But Bastiat will have none of it.

“Life, liberty, and property do not exist because men have made laws. On the contrary, it was the fact that life, liberty, and property existed beforehand that caused men to make laws in the first place.”

This will come as no surprise to those who subscribe to Natural Law. If our rights exist at the individual level, and the protection of those rights is the intent of law, then government plays no intrinsic function.

A Truly Just Government

So, given all this, is a just form of government possible? Bastiat thought so, and for logical reasons, the most forthright and compelling reason being,

“If every person has the right to defend — even by force — his person, his liberty, and his property, then it follows that a group of men have the right to organize and support a common force to protect these rights constantly. Thus the principle of collective right — its reason for existing, its lawfulness — is based on individual right. And the common force that protects this collective right cannot logically have any other purpose or any other mission than that for which it acts as a substitute. Thus, since an individual cannot lawfully use force against the person, liberty, or property of another individual, then the common force — for the same reason — cannot lawfully be used to destroy the person, liberty, or property of individuals or groups.”

It is here that Bastiat does two things masterfully. The first is that he establishes the logical extension of individual rights to a collective group. Though many libertarians will desire to avoid “collective” reasoning or terminology at all costs, this may be an overreaction. As Bastiat clearly states, this sort of collective right is seen as one extending from the rights of the individuals that form that collective, not the collective as an atomic unit. The second is that he demolishes any legitimacy to what must today be 99% of what government and law has been tasked with.

It is here that we should make a distinction between “government” and “the state” as many will use the terms interchangeably. Murray Rothbard, father of modern libertarian theory, in his classic work “The Anatomy of the State” defines “the state” by way of Oppenheimer as the “organization of the political means”. In this context, the “political means” is a reference to the political means of acquiring wealth, the means by which some acquire wealth via political devices at the expense of others. This is as opposed to the “economic means”, the otherwise free system of production and exchange. Bastiat acknowledges this distinct as well later in “The Law” using the term “legal plunder”. So it would appear that on this basis Rothbard and Bastiat would view this just government as something other than “the state” and thusly one can potentially advocate for a stateless society and still allow for organized collective defense.

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations. You now possess a more principled view of the nature and legitimacy of law than 99% of all human beings. I can still remember the day that I read “The Law” (I’m fairly certain that I got through the entire book in a day!) and how I was struck with the simplicity and impregnable logic of Bastiat’s writing. It is, to my knowledge, the most accessible and practical introduction to the concepts of liberty that you could read or recommend to others. So, equipped with this new knowledge, let us renew our minds and be ever vigilant to apply this test anytime we may be tempted to utter those six ill-fated words. And, perhaps, we may also begin to ask ourselves what we can personally do to ensure that no unjust law is ever seen as necessary again.

I like to remind people that there’s no law so small the government isn’t willing to kill you over it. Think of jaywalking: if you make it across the street without hurting anyone or any property, you haven’t morally done anything wrong. But the police will still issue a fine for that, stealing your property. If you rightfully resist that fine, since you did nothing wrong, they’ll try bigger and bigger fines until finally trying to arrest you. You still haven’t done anything wrong, so you resist this attempt to kidnap you and lock you in a cage like an animal. Then they shoot you.

Yes, one can only imagine how few laws most would feel necessary if people expected to have to enforce or carry out the punishment for them personally.