Understanding the history and nature of the modern state of Israel can rank among the most frustrating tasks that one can embark on today. The amount of polarized information and opinions is staggering and it can be difficult, especially as a libertarian and even moreespecially as a Christian, to find information that tackles the subject in helpful ways, from a viewpoint that values non-aggression and handles any Biblical or theological issues properly.

And the Six-Day War is perhaps the most polarizing episode in Israel’s history. Waged between roughly the 5th and 10th of June 1967, the war represents something of a benchmark among wars of the 20th century for what many consider a just, pre-emptive war. Claims abound regarding Israel’s complicity or innocence, with many evoking Biblical imagery of Israel as a “David among Goliaths” or being surrounded with no other choice than to defend itself from almost certain impending attack.

What are we to make of these claims, who is actually to blame, and what is its importance to today? As it turns out, the interim period between Israeli independence (1948) and 1967 itself is rather important in attempting to establish the justice or necessity of the war. So it makes sense to begin here and take a look at how the stage was set for war in the region, beginning with Egypt.

Arab Nationalism and the Spirit of the Age

Normally, we might avoid going too far in depth regarding the actual backdrop of history in these conflicts as they do not always bear too directly on the circumstances themselves. However, in the case of the mid-20th century in the Middle East, this background is critical in understanding the sorts of fears and motivations of those involved.

Recall, for a moment, the state of the Middle East immediately following World War II. Throughout much of the first half of the 20th century, traditional colonial influences and power centers throughout the region were in a state of flux and, with France and Britain recovering from war coming into the 1950’s, much of this influence was continuing to wane.

Israel found itself, indeed planted itself, directly within the midst of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt, and all of these countries had long experienced French or British colonial rule and oversight. But Arab Nationalism began to seriously take hold and sweep the region beginning in the 1950’s and that nationalism was not viewed favorably by any of the Western powers. Take, for instance, the well-known example of nationalism in Iran, with the rise of Mohammad Mossadegh and the British and US response which resulted in regime change and a puppet dictatorship. Similar events in each of Israel’s neighboring countries soon followed and set the stage for future conflict, beginning with Egypt.

Egypt

Egypt, like Palestine before it, had a long history of British occupation and affiliation for much of the first half of the 20th century. But, soon after the 1948 war, Egyptian domestic politics took a very revolutionary turn. During the early 1950’s, mounting anti-British sentiment and actions culminated in the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 and for the next couple of years, these guerrilla activities targeted the British troop presence with the purpose of ending colonial control. Finally, in October of 1954, Egypt and Britain signed an agreement for British withdrawal within the next two years.

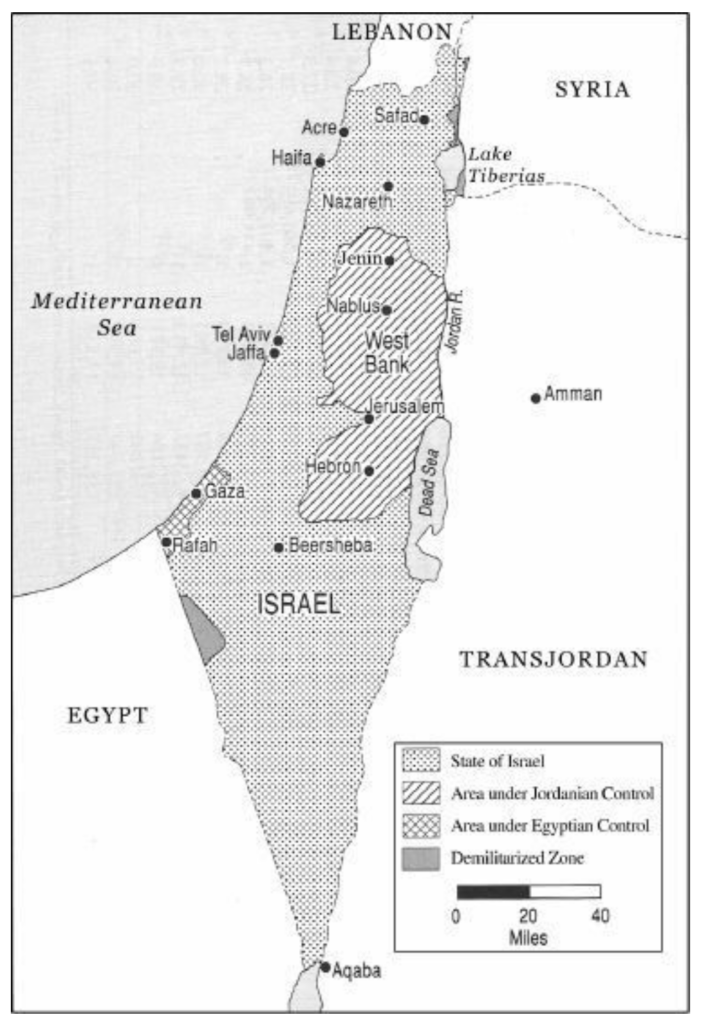

Naturally, the withdrawal of the British presence and control of Israel’s Egyptian neighbor frightened Israel for obvious reasons. At the time, Egypt officially controlled the entirety of the Sinai Peninsula, including the entrance to the Strait of Tiran, as well as the Gaza Strip. The removal of the British influence over Egyptian actions meant that there was a greatly increased potential for belligerence or outright war between the two powers.

But, rather than attempt to pursue traditional diplomacy or peaceful relations, Israel undertook a number of distasteful campaigns meant to either weaken Egypt’s military or political position or its reputation in international eyes. One of those campaigns, begun in July 1954, was a series of bombings in Cairo and Alexandria which targeted US, British, and Western sites. Unfortunately for Israel, the campaign was discovered when one of the saboteurs was caught and tortured, the result being the revelation of the actors and extent of the campaign, after which the remaining members were caught and sentenced. The eventual result of the entire debacle was the Israeli domestic turmoil known as the “Lavon affair”, which resulted in the ousting of then defense minister Pinhas Lavon and his replacement in David Ben-Gurion, back from retirement in 1955. Ben-Gurion’s presence would actually play an important part in shaping events both leading up to and following the 1967 war.

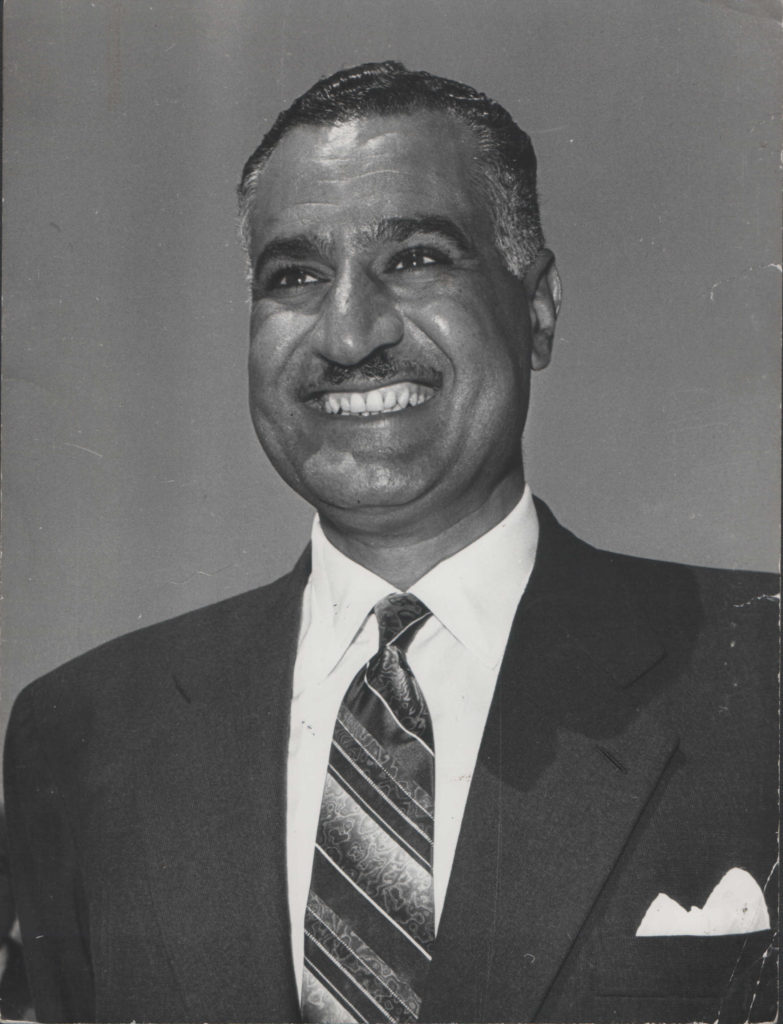

Ben-Gurion definitely feared the potential for Nasser to rise up as a unifying figure that might stand in opposition to Western and/or Israeli interests, opining “that a personality might arise such as arose among the Arab rulers in the seventh century or like [Kemal Ataturk] who arose in Turkey after its defeat in the First World War. He raised their spirits, changed their character, and turned them into a fighting nation. There was and still is a danger that Nasser is this man.” And he was not the only one who felt rather strongly about Nasser’s malign character. After Nasser presided over the Egyptian nationalization of the Suez Canal, then British Prime Minister Anthony Eden, “considered him a reborn Hitler, whose ‘aggressions’ had to be stopped.”

The other path undertaken by Israel against Egypt focused on passage through the Suez Canal and the Sinai region itself. The Bat Galim affair, named after an Israeli ship sent through the Suez Canal in September of 1954, was the first salvo targeting the area. At the time, Egypt had the area tightly controlled against Israeli shipping and it was assumed that any attempt to defy that blockade would result in an unhealthy and damaging reaction against Egypt. The Bat Galim was intercepted, impounded, against international law and accepted maritime conventions, and its crew abused and tortured. Both sides traded blame and barbs regarding the apparent provocation by Israel and the mistreatment of sailors by Egypt. But these next few years would prove to be pivotal to the relationship between the two states. Norman Finkelstein, partially quoting Israeli historian Benny Morris, considers “that ‘from some point in 1954’, Israel’s ‘retaliatory strikes’ were designed to goad Nasser into attacking – what the British ambassador in Tel Aviv called a strategy of ‘deliberately contrived preventive war’.”

The Mood Sours

Tragic in hindsight, the years following 1948 actually saw a variety of potential peace deals be presented and fizzle out for various reasons, but this history was to be hidden from popular view. As Morris summarizes: “The Arab regimes—all of them autocracies or dictatorships—subsequently hid from their constituencies the facts about what had transpired. No Arab archive opened its papers to the scrutiny of historians. In Israel, a democracy, the situation was somewhat different. For decades Ben-Gurion, and successive administrations after his, lied to the Israeli public about the post-1948 peace overtures and about Arab interest in a deal. The Arab leaders (with the possible exception of Abdullah) were presented, one and all, as a recalcitrant collection of warmongers, hell-bent on Israel’s destruction.”

Another constant factor that influenced the relationship between Egypt and Israel was that of Palestinian incursion into Israel. In the years following the 1948 war, the surrounding Arab nations collected much of the resulting outflow of Palestinian refugees. Those Palestinians, unsurprisingly, occasionally returned across the Israeli border, sometimes to retrieve property, sometimes for sabotage, and eventually to terrorize, to one degree or another, the Israeli presence there. From roughly 1948 to 1954, those incursions were very largely non-violent. For instance, Morris cites that armed groups after 1950 increased “largely in reaction to the IDF’s violent measures” and that Israeli casualties were mainly incidental; for example, “of the approximately thirty nonmilitary Israelis killed by infiltrators in 1952, seventeen were civilian guards and two were policemen.”

However, even with the constant threat of border conflict along the Sinai and Gaza Strip, up until January of 1955, Nasser was quite resigned to any kind of overt war or conflict, publishing in “Foreign Affairs” that, “Israel’s policy is aggressive and expansionist.… However, we do not want to start any conflict. War has no place in the constructive policy which we have designed to improve the lot of our people. We have much to do in Egypt.… A war would cause us to lose … much of what we seek to achieve.”

That sentiment would begin to change the very next month. Beginning in 1954, what began as more “innocent” incursions by native Palestinians into Israel progressed into armed and trained trips, directed by and likely green-lit by Egypt, especially within the Egyptian-held Gaza Strip. The tit-for-tat pattern here is a bit hard to suss out in terms of who routinely deserved the most blame but the pattern remained that of slow and steady escalation. The attitude shifted seismically in late February when, after the killing of a single Israeli cyclist occurred three days prior, the IDF embarked on Operation Black Arrow, the raid of an Egyptian army position near Gaza, in which forty Egyptians were killed with almost as many wounded. This would not be the last instance in which Israel seemed to respond in retaliation with a much greater show of force rather than a proportional one and Israel’s noted “retaliatory strikes” would continue to set a precedent that describes Israel’s behavior and mentality regarding Palestinian conflict even to the present day.

The February Gaza raid seems to have catalyzed Nasser’s view of Israel into something much more serious and malevolent than he had otherwise thought. Morris recalls that, “For months thereafter Nasser was to tell almost every Western and UN official he met that the Gaza raid had caused him radically to rethink his position vis-à-vis Israel, which, he maintained, was interested not in peace but in expansion.” Finkelstein also relates the opinion of E.L.M. Burns, then chief of staff of Middle East United Nations forces, wherein he “testifies that before Israel’s raid on Gaza in February 1955, ‘the facts did not indicate … a critical situation’ and that it represented the ‘decisive event [that] set a trend which continued until Israel invaded the Sinai in October 1956’.”

The Sinai Nail in the Coffin

In response to the greatly heightened state of tension that began to exist in 1955, Egypt began sourcing arms from Czechoslovakia in order to bolster their army in the event of further IDF conflict. Israel decided to do the same and, when the US would not supply them, turned to France. And with Nasser having decided to nationalize the Suez Canal against French and British interests along with his support of rebels in Algeria fighting against French rule there, the battle lines were drawn, with Egypt loosely allied with the Soviet Union and Israel, for the time being, with France and Britain. Israel’s plan, then, was one of escalating the situation along the borders and DMZs with the hope of provoking Egypt to respond in such a way as to justify a pre-emptive war: “Ben-Gurion had agreed to a policy of retaliating massively after small border incidents, forcing an Egyptian counterstrike, which would provide Israel with the pretext to go to war and destroy the Egyptian army before it absorbed its new Soviet weaponry and became too strong.”

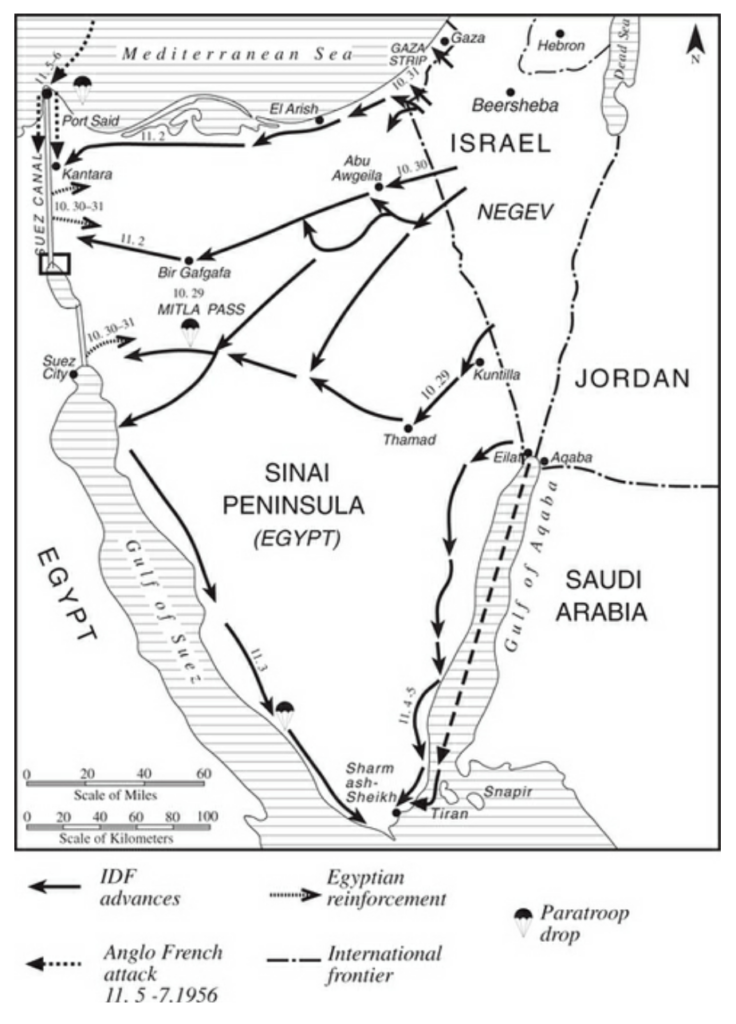

The secret Sevres Conference of October 22-24 cemented Israel allying with Britain and France to invade the Sinai Peninsula. The plan was to have Israel drop paratroopers along the Suez Canal zone with Israeli armor charging across the Sinai to meet them and for Britain and France to intervene and “save the day”, as it were, to broker peace between the inevitable Egyptian-Israeli clash. The operation began on October 29 and within the next dozen or so days, the Egyptian military was decimated, with its entire air force almost completely destroyed, and the Sinai and Gaza Strip effectively under Israeli control. Israel’s aim seemed to be, “to ‘destroy Nasser’s prestige’, nipping in the bud the twin bogies of Arab independence and modernization”, and this was perhaps gained in some measure.

But the Western powers of Britain and France were not so lucky, with the plan severely backfiring. Nasser, who predicted the Anglo-French plans at the time, and Israel agreed to a ceasefire well ahead of the impending allied invasion, rendering the plan effectively aborted. Morris considers that, “Both Britain and France suffered irreparable harm in the Middle East as a result of Suez. Their position as coprotectors of Western interests in the region was largely taken over by the United States. For decades the stigma of (incompetent) neo-imperialism was to stick to them. As expected, the Soviet Union made further inroads, pouring money, arms, and advisers into a succession of ‘progressive’ Arab states.”

Morris also the cost and effects of the Sinai Campaign:

“The Israeli conquest and its aftermath were characterized by a great deal of unwarranted killing, especially of retreating or captured Egyptian soldiers. In all, Israeli troops killed about five hundred Palestinian civilians during and after the conquest of the Strip. About two hundred of these were killed in the course of massacres in Khan Yunis (on November 3) and in Rafa (on November 12). Several dozen suspected fedayeen who had fallen into Israeli hands were summarily executed…The IDF lost about 190 soldiers killed, 20 captured, and 800 injured in the Sinai Campaign. The Egyptian army lost several thousand killed and much of its equipment. Some four thousand Egyptians fell into Israeli hands.”

The invasion also seemed to further tarnish the reputation of Israel in international eyes. Then Soviet prime minister Nikolai Bulganin related to Israel that their invasion of the Sinai, “was sowing a hatred for the State of Israel among the peoples of the East such as cannot but make itself felt with regard to the future of Israel and which puts in jeopardy the very existence of Israel as a state.” As well, the UN quickly issued a UN General Assembly resolution calling for the immediate withdrawal of Israeli, French, and British forces from Egyptian territory which passed 65 to 1, Israel being the only dissenting vote and, fittingly, with France and Britain abstaining.

The Bottom Line

And all this in the span of only eight years after Israeli independence. Though it would be convenient to simply limit our scope to the prevailing conditions of 1967 itself, to leave out the history of these early years would be to lose an amazing amount of relevant perspective required to understand the true nature of what the Six Day War represents, with all its prospects and its baggage. In the next part of our series, we will consider the similar time period and events that were occurring in Syria and Jordan at the time and continue to set the stage for what would eventually unfold.