In the first three parts of our series, we took a look at the events leading up to the Six Day War in each of the major countries surrounding Israel, that of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. Each of these nations experienced a great deal of change following the World Wars and the sweeping Arab Nationalism that resulted from the breakdown and retreat of Western imperialism during the mid-twentieth century and each represented a unique opponent to Israel for its own unique reasons.

It is not too difficult to predict, especially in hindsight, why events played out the way they did in June of 1967. But the situation reached a fever pitch in the few days and weeks just prior to war and the justifications given in defense of Israeli actions generally relate to this much narrower timeframe. Those justifications are varied but two of the primary justifications center around Egyptian actions at the time, mainly the remilitarization of the Sinai Peninsula and the later blockade of Israeli shipping through the Straits of Tiran. But how do these justifications measure up to scrutiny?

Trouble In the Sinai

When last we left our view of Egypt, Israel had just invaded according to the prior agreement made with British and French forces. As it were, that plan fizzled before it could be fully implemented which left the Western powers with egg on their face and a half-cocked and executed plan on the ground. The canal now closed due to sabotage and the statue of Ferdinand de Lesseps, planner of the Suez Canal, blown up, British and French forces agreed to withdraw but only after the establishment of a UN force to assist in that evacuation and secure the region. Thus, on November 7, the General Assembly created the UN Emergency Force, or UNEF. This force would go on to play a very prominent role in the short weeks leading up to June of 1967. The entire debacle also cemented US primacy as the respectable Western power of choice for the region. And the opportunity was taken up quickly by the Soviet Union to be the token “anti-imperial” or “progressive” ally of Arab states that did not or could not ally themselves with the West.

But, more than anything else, the Sinai Invasion marked the pivotal event that galvanized Arab ire behind an apparent enemy and soured any goodwill that had been built toward Israel. As Benny Morris concludes, “If the destruction of Israel was not Arab policy before, after 1956 it most certainly was. While border clashes and terrorist infiltration remained rare during 1957–62, the political will to belligerence had vastly increased in the Arab world as a result of Israel’s collusion with the ex-imperialist powers and the onslaught against Egypt. What many Arab leaders had long claimed had now been ‘proved’—Israel was the imperialists’ cat’s-paw in the Middle East.”

Originally, Israel had no intention of leaving the Sinai territory and also promised that no UN/international force would be stationed there. In stark contrast to the US-Israeli relationship today, Herbert Hoover Jr, the Secretary of State at the time, actually threatened that, if Israel did not withdraw, the US would cut off all aid, public and private, to Israel, subject them to sanctions, and expel them from the UN. Israel bowed to the intense pressure the next day but withdrawal was slow and petulant. They retained Sharm ash-Sheikh and the Gaza Strip, and anything of value in the peninsula was either dismantled and taken back with them or destroyed.

But further months of pressure eventually found Israel withdrawing even further from both locations and this sets quite the stage for further events and the justification for Israeli actions against Egypt in 1967. In early 1957, the United States offered a number of indirect and/or vague promises to Israel addressing their concerns regarding withdrawal from Sharm ash-Sheikh and the Gaza Strip. In exchange for guaranteeing their right of passage through the Straits of Tiran (with apparently little thought as to their own right or ability to do so) as well as the potential promise to establish UN administration in the Gaza Strip to avoid further violence there, Israel agreed to withdraw from both. UNEF would also remain and be stationed along the Egyptian border in only Egyptian territory.

Justification 1: Egyptian Militarization of the Sinai

Followers of this series will recall that April and May of 1967 were particularly tumultuous months leading up to the war. The end of 1966 saw a large-scale raid in the West Bank town of Samu, then Jordanian territory, while the state of conflict along the Israeli-Syrian border had flared to become a media focus in April. All the while, Egypt had stood by and failed to act in any meaningful way. But eventually, criticism of his inaction led Nasser in mid-May to push forward in response and move once again into the Sinai Peninsula as well as call for the removal of UNEF forces there and in Gaza. Then UN Secretary General U Thant obeyed without much of a response which seemingly surprised both Israel and Egypt.

These actions have long been considered a core justification of Israeli actions during the Six Day War, both as a sign of Egyptian aggression and intentions. There is, however, quite a bit of necessary framing and response to these actions.

The first is that, though taken in isolation it may appear that, as the likes of Abba Eban have claimed, the Egyptian militarization of the Sinai was “one of the most unprovoked actions in international history,” seen in context with the state of Israeli military affairs in the region, it is certainly less so. The large-scale actions undertaken at the time by Israel and the war rhetoric of the time provide a stark contrast to visions of an innocent and helpless Israel. As well, many of those observing the situation saw Nasser’s actions as, though ill-fated, rational and inevitable. Odd Bull, noted UN official, thought that Nasser “was obliged to act if his reputation in the Arab world was not to suffer, because he had been subjected to a lot of criticism on the ground that he was sheltering behind UNEF.” Much to Nasser’s chagrin, U Thant had not pushed back and offered no piecemeal withdrawal leaving Nasser with the only options to proceed with full UNEF withdrawal or none at all. As well, Moshe Dayan himself thought that “the nature and scale of our reprisal actions against Syria and Jordan had left Nasser with no choice but to defend his image and prestige in his own country and throughout the Arab world, thereby setting off a train of escalation in the entire Arab region.”

The likelihood or intent of Egyptian invasion of aggression towards Israel is also suspect as a number of factors speak to quite the opposite being true. For one, though Nasser expelled the UNEF forces present at the time, there was a precedent for an earlier commissioned force as part of the Egyptian-Israeli Mixed Armistice Commission (EIMAC) that could have functioned as an analog. However, though Egypt expressed a desire to reactivate the agreement in the intervening period prior to June 5, Israel rejected the proposal. As well, the original intent and expectation for UNEF forces would be that of UN presence on both sides of the Egyptian-Israeli border. But, while Egypt had acceded to their presence on their side, Israel had not, and despite pressure from the US, Britain, and Canada, all proposals to reactivate UNEF on the Israeli side of the border were also refused by Israel. As U Thant later opined, “if only Israel had agreed to permit UNEF to be stationed on its side of the border, even for a short duration, the course of history could have been different. Diplomatic efforts to avert the pending catastrophe might have prevailed; war might have been averted.”

And in early June, US officials met with Egyptian officials in what was considered to be a promising agreement to allow World Court arbitration of the blockade of the Straits and a potential easing of the oil blockade of Eilat. As further good faith, Egypt even agreed to send their own vice-president to the US to explore a diplomatic settlement within the week. Despite this obvious direction toward non-violent mediation, Israel executed its planned attack before any conclusion could be reached. As Dean Rusk, then US Secretary of State related, “when the Israelis launched the surprise offensive. They attacked on a Monday, knowing that on Wednesday the Egyptian vice-president would arrive in Washington to talk about re-opening the Strait of Tiran. We might not have succeeded in getting Egypt to reopen the strait, but it was a real possibility.” If, indeed, as Abba Eban purports, “Israel has never worked harder to prevent a war than it did,” it seems strange that it would repeatedly reject measures and short-circuit diplomatic resolutions that held the promise of doing just that.

In the words of Israeli Mossad chief Meir Amit, “Egypt was not ready for a war; and Nasser did not want a war.”

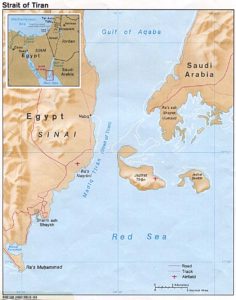

Justification 2: Blockade of the Straits of Tiran

In addition to the supposed threat posed by Egypt’s remilitarization of the Sinai Peninsula, the subsequent blockade of the Straits of Tiran on May 23 is also commonly used as justification for Israeli actions during the war. Abba Eban, one of Israel’s staunchest defenders in justifying the nature of the Six Day War, considered that the blockade represented an “attempt at strangulation” and “act of war.” While it most likely was an attempt at least at inconvenience, it was certainly a provocative action. Whether or not it represented a dire threat to Israel’s short-term security or survival as well as whether it foreshadowed some ulterior motive must be proven.

We have already seen how Israel’s refusal to allow the return of Palestinian refugees after the 1948 war motivated much of the Palestinian and Arab antagonism shown toward Israel. This was also the given justification for Nasser’s reasoning for the initial blockade of the Straits the first time, prior to the Sinai Invasion of 1956. As we noted before, Israel had received some vague notion of US commitment to freedom of passage for Israel through the straits but this does not appear to have been upheld or considered viable by those close to the situation. Effectively, then UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold considered that Egypt’s sovereignty should effectively be “re-established by a withdrawal of troops, and the relinquishment or nullification of rights asserted in territories covered by the military action and depending on it,” and that the Israeli withdrawal was “unconditional in accordance with the decision of the General Assembly.” This was echoed by the US at the time as well, who considered that occupying powers could not themselves impose conditions on their withdrawal.

This largely left the legal issue of Egyptian actions unresolved. As a matter of input into the matter, the Harvard Law Professor Roger Fisher did provide quite a lengthy review at the time of the legal situation surrounding passage through the straits. Though no one legal opinion is necessarily authoritative, he considered that “The United Arab Republic had a good legal case for restricting traffic through the Strait of Tiran,” and that, “it is debatable whether international law confers any right of innocent passage through such a waterway.” He noted that Egypt/the UAR had not signed onto the 1958 Convention that would ensure such innocent passage. And he also noted that the “right of innocent passage is not a right of free passage for any cargo at any time. In the words of the Convention on the Territorial Sea: ‘Passage is innocent so long as it is not prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal state.’” In light of Israeli actions of the time, it’s raids in Jordan and escalation in Syria, it is reasonable to conclude that allowing such passage of materiel could have been seen as aiding their ability to continue such actions.

This murky legal situation was undoubtedly what led countless UN and US officials to favor World Court or international court arbitration to more definitively settle the matter, but potential legal arbitration was rejected by Israel along with the other proposals offered for diplomatic resolution. And this is, indeed, what Nasser agreed to and began to pursue prior to the initiation of the war. Certainly, at any rate, the US State Department noted that, as paraphrased by Finkelstein, “A blockade…did not of itself constitute, an armed attack, and self-defense did not cover general hostilities against the UAR.”

It also appears that the Israeli picture of the importance or necessity of trade through the port of Eilat was quite overblown in the face of the blockade. Eban again describes the Israeli experience from the blockade as “drastic – slow strangulation or rapid, solitary death.” But the terms of the blockade were limited to Israeli-flagged vessels and any other vessels carrying strategic cargo. Finkelstein relates that “according to the UN Secretariat, not a single Israeli-flagged vessel had used the port of Eilat in the previous two and a half years. Indeed, a mere 5 per cent of Israel’s trade passed through Eilat.” Oil was one of the major categories forbidden from passing through to Eilat but this could also have been delivered via other routes. The actual rigor of the blockade was also highly suspect. Indar Rikhye, commander of UNEF at the time, noted that the “navy had searched a couple of ships after the establishment of the blockade and thereafter relaxed its implementation” along with citing a number of supporting examples.

The Bottom Line

We have seen that, in the case of Israeli claims against Egyptian actions at the time, warrant of pre-emptive war begins to appear overblown and unsubstantiated. It is easy to see how one-sided accounts of these events may color ones’ reaction toward favoring Israel while the actual situation on the ground is far more nuanced. But these are not the only justifications given for the war and in our next installment we will address others related to Israeli motivations and claims regarding the West Bank and Syria.